While the academic year is starting up in many places, here in Greece the summer is still winding down. For me, this means having the time to finish up the projects I’ve been working on over the summer months.

One of these was the ethnographic fieldwork I conducted this July in Zakros, a village on the very eastern edge of Crete. Dr. Ioanna Antoniadou, an archaeologist and professional ethnographer who is collaborating on the project, helped develop the research plan based on the model of Rapid Ethnographic Assessment (REA). We wrote up a questionnaire that targeted the most important research questions we wanted to ask, printed off a stack of consent forms, and headed to Zakros in mid-July. This happened to coincide with the peak of the tourist season and a period of agricultural downtime while the olives matured.

Overlooking Kato Zakros, the main tourist destination in the area

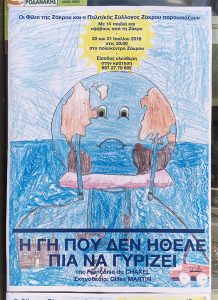

Over two weeks in Zakros, Ioanna and I chatted with the people who spent their mornings in the kafenios (most often men), met with local business owners and community representatives, and toured the local agricultural cooperatives. We attended a play put on by the local schoolchildren, with organizational and financial backing from a French non-profit, Les Amis de Zakros. The questionnaire that we had developed was soon set aside in favor of guided conversations, which were generally more fruitful. But one thing our interviewees seemed to like was a game in which they arranged cards – each with the name of a kind of traditional agricultural feature (like “watermill” or “terrace wall”) – based on how old they thought the features were.

We came away with 16 recorded interviews and pages and pages of notes from our conversations with the Zakrites (that is, “people from Zakros”). Our youngest interviewees were born in the 1990s, while our oldest were born in the 1930s. The latter had lived through World War II, the Civil War, and all the rapid technological transformations that started under the Junta in the 1970s. They remembered when the road to Zakros was paved (in the 1950s), and when the first television appeared (in the 1970s!). They also remembered when the archaeologists began digging the Minoan site of Kato Zakros in earnest in the 1960s.

Freshly cleared olive grove in Gonia, near Zakros

There’s a lot that I could write about: our experience as female interviewers (and as outsiders, to boot), our difficulty finding women to interview, the UNESCO Global Geopark that the local community has worked so hard to develop in Sitia, or the local attitudes towards neoliberalism and the encroaching threat of wind turbine construction. For now, I’ll focus on the two biggest themes that emerged from our interviews: the sense of isolation from the rest of Greece, and the connection with the area’s Minoan past.

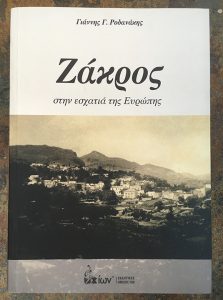

Zakros at the Edge

On our first day in town, Ioanna and I found out that a local historian had written a book about the area, called Zakros: At the Edge of Europe. Many of the men in the kafenios were talking about it. By the end of our trip, we realized just how deep an impact the book had had on the local historical narrative (or at least the versions we heard). Anyone who knew anything about the Venetian and Ottoman periods had read this book and digested its information, incorporating it into the stories they weaved for us.

At the same time, the book pointed out how Zakrites and foreigners alike conceive of Zakros’ place in the broader geopolitical landscape. To put it simply, Zakros is really far away from everything. The nearest major airport is in Heraklio, 3 hours by car. The highway from Heraklio stops after Agios Nikolaos, and the rest of the journey follows a series of narrow and terrifyingly windy roads. The capital of the region, Sitia, is only an hour away, but it starts to feel a lot further once you want to see a doctor or shop at a supermarket – both of which can only be found in Sitia.

Person after person who we interviewed came back to this point: an identity based on isolation. In many interviews, this came across as a feeling of abandonment by the local and European governments, or as a sense of being forgotten while the rest of Crete touristified and developed its vacation infrastructure. But most of the time, people highlighted isolation as the region’s most valuable characteristic. Invaluable, let’s say, because once lost, it could not be easily retrieved. There was lots of discussion about how to capitalize (literally) on this isolation in order to attract more tourists, or maybe better-quality tourists… or perhaps tourism wouldn’t really bring a lot of benefit to the farmers, so instead the isolation should be used to market all the olive oil the area produces. (As you might guess, there were a lot of different opinions on this topic.) Ultimately, isolation emerged as one of the most central themes in the interviews we conducted.

The Minoan Connection

One of my main questions at the start of the project was about how modern life connects with the archaeological past. We went to Zakros hoping to learn more about locals’ attitudes toward the material remains of the Venetian and Ottoman periods – the churches, houses, threshing floors, and cobbled footpaths (kalderimia) that dot the landscape and form the heart of several abandoned villages in the area. For the locals, as it turned out, the “archaeological past” overwhelmingly meant the Minoan past. All the stuff and all the history from the last few centuries might very well be a part of the “traditional past,” but it occupies a much smaller place in the narrative that the Zakrites tell about the region.

Farming equipment and other relics of traditional lifeways at the Zakros Museum of Water and Waterworks

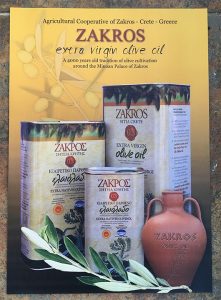

One of the most obvious ways that locals connect to the Minoan past is through marketing. For the most part, this means the marketing of olive oil, the most important agricultural export from the region. Consider the official seal of the Agricultural Cooperative of Zakros: a circular stamp with a Minoan vase at its center. The Cooperative’s informational pamphlets draw direct connections between the olive-harvesting techniques of the Minoans that developed 3,500 years ago and the modern technologies employed today. Their YouTube video (in English) is definitely worth checking out.

Aside from the olives, many of the people we talked with made this connection in a different way, focusing instead on the region’s settlement history. The Minoans used to live at scattered sites all around the palace at Kato Zakros. They constructed a complex water system to bring water from the springs above, carved into mines along the coast, and used the gorge leading down to Kato Zakros (the “Gorge of the Dead”) as a cliff-side burial ground. What happened after the Minoans left – and why it took so long for the region to be reoccupied – are questions that still have no definitive answers.

But while a few people found these questions captivating, the archaeological past was a fairly small part of our conversations overall. The name “Kato Zakros” might evoke a vision of Minoan splendor for foreigners (especially of the archaeologist variety), but to many of our interlocutors, the place recalled the banana groves, kafenios, and customs house that used to grace the shore long before the excavations began.

Pointing the way to the oldest olive tree in Zakros

0 Comments